Introduction

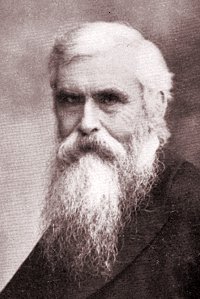

Born: May 15, 1823, Fenny Stratford, Buckinghamshire, England.

Died: March 23, 1906.

Born: May 15, 1823, Fenny Stratford, Buckinghamshire, England.

Died: March 23, 1906.

Harris’ parents were strict Calvinistic Baptists and very poor. When Harris was five years old, his parents emigrated to America, settling in Utica, New York. His mother died when he was still a young boy, and Harris was forced by circumstances to help support the family from the age of nine.

At age 21, Harris became a Universalist minister, preaching to the congregation of the Fourth Universalist Church in New York City. In 1848, he became minister of an independent Christian congregation in New York City.

In that church he came into contact with young newspaper publisher Horace Greeley, who was so moved by one of Harris’ sermons that he was inspired to organize Harris’ congregation to help found the New York Juvenile Asylum.

Harris soon turned towards spiritualism, becoming a devotee of the Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg. By 1851 he had left New York for Virginia where, together with J. L. Scott, he launched the first of his communal enterprises, the Mountain Cove Community of Spiritualists, on pristine land claimed by one of the group’s leaders to be the actual site of the Garden of Eden.

It was intended to there create a city of refuge

from which angels were to descend and ascend. The experiment proved to be short-lived, however, racked by squabbling over property and personalities, and after two years the Virginia religious commune collapsed.

Following the demise of the Mountain Cove Community, Harris returned to England, where he preached modified Swedenborgian ideas to a London congregation for several years.

There he began his career as a writer and poet, publishing several books. Harris’ poetry was well regarded, and he was made the subject of a chapter by Alfred Austin in his book The Poetry of the Period.

Harris subsequently returned to America, settling in Amenia, New York. He stayed at Amenia five or six years, establishing a bank, a flour mill, and a vineyard and gathering around him a small group of devoted religious disciples.

Included among the approximately 60 converts were five orthodox clergymen and about 20 Japanese from Satsuma Province, among others. The community—the Brotherhood of the New Life—decided to settle at Brocton, New York, on the shores of Lake Erie.

Its nature was co-operative rather than communistic, and farming and industrial occupations were engaged in by his followers, numbering at one time about 2,000 in the United States and Britain.

Harris took part of the community to Santa Rosa, California, where he created the Fountain Grove community around 1875. In 1891, he announced his body had been renewed, and that he had discovered the secret of the resuscitation of humanity.

Eventually a fire destroyed large stocks of his wine, and he remained in New York till 1903, when he visited Glasgow, Scotland.

His followers believed he had attained the secret of immortal life on earth, and after his death in 1906, declared he was only sleeping. It was three months before it was acknowledged publicly that he was really dead.

Not all were as enamored of Harris as his followers: An article in the December 18, 1891, issue of the Literary World, page 527, examined their belief in him, concluding, Verily the credulity of man is unfathomable.

If you know Harris’ burial place,